|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

|

MORE Life

|

|

Mail artists use postal system

as medium while avoiding envelope Copyright 2006 Houston Chronicle

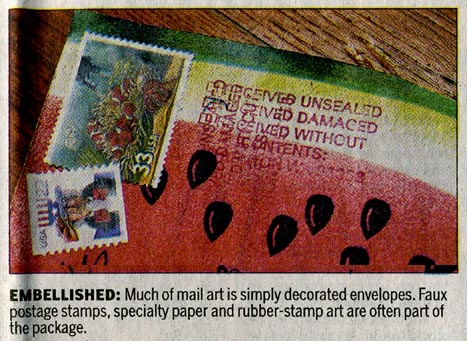

BETH Jacobs marvels at her mail. With good reason. She's never sure what might turn up. It could be a pink plastic toy brain or a Pringles can. A glow-in-the-dark alien or a wooden-handled purse. An egg carton or a squishy Halloween-decoration pumpkin head. A license plate or a pizza box. She's found all of them in her West University Place mailbox at some point, with canceled stamps and clearly printed mailing labels. But none arrived in a box. For mail artists, the medium is the postal system. One thing they all have in common? Naked white envelopes make their skin crawl. Jacobs and her correspondents surprise each other with offbeat mail. "We're all so used to going to the mailbox and grabbing a wad of bills, so it's so nice when you go out to your mailbox and you don't know what you're going to find there. Especially when it's something someone has made for you." Another of her treasures, a green plastic hat — the kind worn by St. Patrick's revelers who've consumed too much green beer — got through the postal system with 43 cents postage. No box. No beer. Often, mail art is about what's not there. It's a conceptual-art movement with no membership, organization or leaders. Mail artists form loose networks, but they're not clubby types. In fact, they tend to abhor formal groups as much as they do an unadorned envelope. Paola Morsiani, curator of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, said mail art springs from the Utopian idea that everyone can make art and that art connects people all over the world.  "What I find interesting is that it's a precursor to Internet art, which also involves making a connection," she says. The Contemporary Arts Museum in 2002 presented an exhibition of the work of Alighiero e Boetti that included his mail-art projects. "It's not something that most artists would specialize in," Morsiani says. "Usually, it's just one form of expression an artist would use." Mark Jetton, manager of Salado Stamp in Salado and a former Houston resident, is one of Jacobs' most faithful correspondents. "We're an odd lot," Jetton says. "Mail art is hard to understand. I'm not so sure it is art; it's probably not good art." One year, around Halloween (prime shopping season for mail artists), Jetton found fake rubber hands and feet at Big Lots and, realizing their potential, bought several of each. "I cut a hole in the box and made the hand come through and I secured it very well, addressed the top of the box, took it to the post office. They oohed and aahed; they couldn't believe it." He also sent a friend awaiting foot surgery a foot version, with toes sticking out of the box. He's been on the receiving end of oddities, too. "I have gotten a coconut in the mail, just a coconut with a label attached," he says. "It was hairy, it was very strange. I don't know what the postman thought." Jacobs and Jetton agree that befriending postal workers is one key to success. "If you know them, you feel like they'll take good care of it," Jetton says. "Once it goes behind that wall they may jump up and down on it for all I know, but I've had very good luck with the mail. People complain about the price of stamps, but to me it's amazing that for 39 cents you can drop a piece of paper in the mail, it goes across the country, and someone else gets to see it a few days later." Well, usually a few days later. It'll generally get to its destination, but there's no guarantee how quickly. A mask Jacobs fashioned from handmade paper and decorated with fringe took three weeks to travel a mile. But it arrived in perfect condition. "I can't show you my very best art, because it's somewhere else on the planet," she says. Part of the fun is entertaining postal workers. "The post office is so boring and regimented and restricted and conformist," Jacobs says. "We like to bust up the routine of the postal workers. White envelopes are just abhorrent to the mail artist's nature." After Sept. 11 and the mail anthrax scare, mail artists tended to get more conservative and follow basic rules in hope of bending them. New York graphic artist Mark Bloch rode one of mail art's waves of popularity in the mid-'70s as a college student at Kent State University in Ohio. Although mail art has influenced his whole career, he says some of the thrill is gone because postal workers are increasingly suspicious. "I used to love to appear at the post office window with five weeks' worth of mail," Bloch says. "There was a whole performance-art aspect to it. Now anything unorthodox — they don't want to send it." Bloch recently sold and donated boxes of archived mail art to New York University's Downtown Collection. Most participating artists have similarly large collections of it piled in their homes or studios. Three-dimensional mail is just one aspect of it. Artists also embellish envelopes and postcards or send a work in progress, to which recipients add something of their own and pass it along. Some create their own stamps, which are canceled along with the real postage. Many incorporate rubber stamping. "In a way it's a very important art movement, but it's kind of below the radar by its very definition," Bloch says. "It has missed a certain amount of the historification process, and that's good, because it was never about superstars. Some people have said mail art is the largest, most widespread art movement ever to come along. It's existed at least from 1955 until now, 50 years." Participants follow in the tradition of Dadaism, the Surrealists, Marcel Duchamp, the Fluxus group and Ray Johnson. "Fluxus has a lot in common with mail art," Bloch says. "It had artists that used the mail in a big way — and it was a parallel development with Ray Johnson, the guy who invented mail art, more or less. I say more or less because he didn't really call it mail art." Johnson's work came to be known as the New York Correspondence School. Johnson was friends with the Fluxus artists, pop artists and Abstract Expressionists, but he didn't want to be identified as part of an existing group. "Instead of making large-scale art in the '60s, Johnson cut his art into pieces that would fit into an envelope," Bloch says. "He would take collages and cut them up and send them all over the world, ask people to add to them and send them to somebody else." Articles in Rolling Stone and Art News in the early '70s led to an increase in mail-art output among American art students. "You could follow these spikes around the world," Bloch says. "Right now Spain is huge into mail art. They are in their golden age of mail art. China may be next. The original idea — no galleries, no museums, the address is the art, anyone can do it — is very attractive to young people, and when they hear about it they want to do it." Jacobs has taught classes in Houston on mail art, including a workshop on how to dress up Velveeta boxes, a skill for which she is famous — in certain (weird) circles. But mail art wasn't always second nature to her. The first time a three-dimensional object was delivered to her, she threw it away — accidentally. A friend had sent her a plastic Coke cup, which she found on the front lawn. Annoyed, thinking it had been dropped by construction workers, she tossed it in the trash. Later a family member noticed her name on it. The postal carrier had left it on her front steps and it likely fell off the porch. It was filled to the brim with toys. Bloch has sent and received his share of weird mail over 30 years, too. He's gotten a piece of the Berlin Wall, a brick, a piece of toast, a platform shoe long after disco had died. He has mailed home fries from Jerry's Diner in Kent in a soggy box. And there's this: "Me and a guy who went by the name of Zona in western Massachusetts once mailed a plucked dead rooster carcass sealed in plastic to a guy in San Antonio. He said some dogs found it in his mailbox and carried it off. We never found out if this latter part was true or an urban mail-art myth but I swear to you the rooster was mailed."

|

|||||||||||||||