An Interview with the late Hugh Hopper

by Mark Bloch

The Knitting Factory

New

York City

September 6,

1998

June 9, 2009--Hugh Hopper, underrated songwriter and the late great bassist for the Soft Machine and a great many other bands, passed away this week after a battle with leukemia. Here is an extended interview I was privledged to do with him in 1998 on a late summer's day between two gigs at New York's Knitting Factory. The first was the U.S.A. debut of Brainville with Daevid Allen, the late Pip Pyle and Kramer and the second, a few days later, was a tribute to Robert Wyatt with a wonderful array of performers from Fred Frith to Karen Mantler. Hugh and I covered much of his wonderful career in this conversation and I was grateful to ask him these questions after decades of enjoying his contributions. We will miss him and his unique musical inventions. His playing and compositions on The Soft Machine Volume II remain unparalleled in music history!

Mark Bloch: The Soft Machine really drew me into the avant garde. You guys were a big influence on me. So it's great to finally meet you.

Hugh Hopper: Here I am!

|

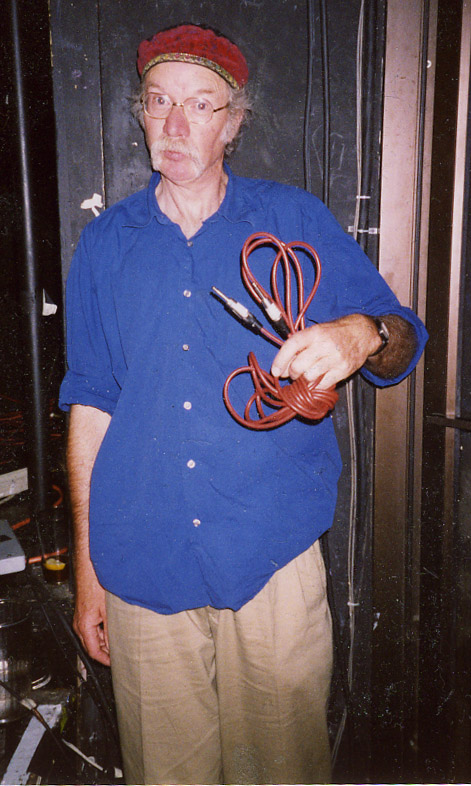

| Hugh Hopper, pausing to mug for the camera while gathering up chords and cords, after a gig at the Knitting Factory in New York in 1998. (Photo by Mark Bloch) |

Ever since you made that 1984 album, I've always felt you were the most "out there" of all the Soft Machine musicians (and that's really saying something!) Yet, I hear the last time you came to New York you played a bunch of James Brown songs. Is there a pop side of you I'm not aware of?

I used to... I still do... love James Brown. But the last time I came to New York, I was playing with Kramer. So in fact, no, in fact we were doing even weirder things. Because Kramer had this set that he wanted to do, of his songs, but also a couple of things like a Roy Orbison song and also we did a Lennon song- the Jealous Guy. Stuff like that. That was Kramer's gig. We were going to Japan and he wanted me along. So really, that was a Kramer gig, that wasn't my gig. But yeah, I'd be happy to do James Brown.

But do you like pop music? I remember reading somewhere you brought a pop sensibility to the Softs.

I'm so mixed, anyway, now. There are so many influences. Like everybody else, I started listening to the radio when I was--whatever--13, 14, and hearing all this stuff. And at that time, when I was that age, it was things like Chuck Berry and Little Richard and stuff like that. Even Presley, things like Presley. I mean, I hated Presley later on but the early stuff... it probably had to do withÉ It was just the first time I'd heard electric guitar. I mean, Scottie Moore playing electric guitar on those early Presley records... I mean that was the beginning, probably, on my soundscape. As big as other things like John Coltrane, later on, and Ornette Coleman and stuff like that. But when I was 14, I had never heard an electric guitar before. I mean, you can't understand that now because the electric guitar is such a part of life, but then, it wasn't. It was like a dirty word. Especially in England. It was a dirty word and a dirty thing to do. Because it was a whole modern thing-- of rock 'n' roll and electric guitar. "That's the American stuff. Send it back across the Atlantic." Because people, in fact, still had a hangover from the Big Band ages and crooners and stuff like that. Things like Bing Crosby, and the English version-- which was terrible-- that's what the Hit Parade was, before things like Presley and Bill Haley that came across in the Fifties.

So for you that Hit Parade was interrupted-- first by the electric guitar and then, later, by the stranger jazz?

That's right.

The jazz after the electric guitar?

Well after. Yeah, I started playing guitar. Actually, my brother started before me. He's two years older so I always followed him in music for a couple years. And then I took up bass. And the very first, kind of, things we were doing was stuff like Chuck Berry numbers and Little Richard numbers.

So you played the bass and your brother played the guitar?

That's right.

And was your father a musician too? Is that right?

Not really, no. I mean both my parents played. As people that age did, they played the piano. People learned the piano when they were kids. They played the piano much further than I ever learned to do because I never had lessons. But yeah, they were very musical. There was always music in the home. You know, on records or on the radio. Light classical stuff, middle-of-the-road classical stuff. So yeah, my father wasn't ever a musician but both my parents loved music.

And Richard Sinclair told me he came over your house, once, because he heard you had a bass?

Yeah, that's when we first started getting the band together, Wilde Flowers. It was Robert Wyatt, Kevin Ayers...

But that was before that, right?

It was about the same time.

Wasn't that the first thing that happened? How did it all actually begin?

I think Richard... No, thatŐs right. Because I started playing with Robert and Daevid, actually, first. It was the first musical thing I really did outside of playing at home with my brother. Which then developed into a kind of avant garde, jazz thing. And it was after that. We had decided in 1964 that it was OK, suddenly, to play-- because the Beatles were so big-- that it was OK to play songs again and stuff like that. But it was after a while, actually. OK, so that was '62 and my brother and I were playing rock and roll at home.

Just the two of you?

In fact there's a tape of the two of us doing that. Playing songs like ThatŐs Alright, Mama, Kansas City, all that kind of stuff.

Did you have an electric bass or a stand up bass?

No, an electric bass. OK... that's the first moment, kind of thing. And then after that, I got involved with Robert again. I'd been at school with him but he'd gone off and left school earlier than me. And I got ahold of him again and started listening to jazz and Ornette Coleman. I actually came from the other end of jazz. I didn't know anything about jazz at all I didn't know you were supposed to go through mainstream jazz and then later get to the far out stuff. Unlike many people my age, I listened to the wrong stuff first and then worked backwards. I didn't know anything about the technique of jazz or what was happening at all. I just liked the sound of it. I liked the sound of Charlie Haden on bass and Ornette Coleman, of course, and stuff like that. So I started getting into that, started playing with Daevid and Robert and Mike Ratledge. Yeah, then that was about it. It sort of became respectable to play songs again. After things like the Beatles it was OK.

So then we set up Wilde Flowers and then we invited Richard along, I think. In fact, his father knew my father. We lived in the same town and his father was a bass player, in fact—RichardŐs father-- so that's how that connection came about. But I think we'd already started with Kevin Ayers and Robert just trying to play stuff. Kevin played a bit of guitar but didn't really know many chords or many... Richard knew all the chords of all the songs. He was a great technician on the guitar.

He was?

Yeah, even then, yeah. He was 16 years old he knew all the Beatles songs, all the chords immaculately, you know. I don't think-- he wasn't, actually, playing bass, then, at all. He didn't play bass until much later.

Do you remember when Kevin and Daevid came around to Robert's house? Because they came from elsewhere, right? And you were in school with Robert. So do you remember them coming on the scene?

Yeah, in fact, because Daevid came from Australia so, I mean, he came to England and Robert's parents had a-- it wasnŐt an enormous house, but it was a quite a big house-- in the country outside Canterbury. But they didn't have any money because Robert's mother was a writer-- and you know the problems with writers-- so they used to let out rooms to passing strangers, hoping to get some money. But, of course, most of the strangers didn't have any money either, so they didn't get paid. But they got some interesting people there. So that's how Daevid came to meet Robert.

And Kevin was actually in school-- a private school-- fairly near where Robert lived. I think that's the connection how Kevin got to meet Robert. Although Kevin was from the region, from the area, just because he was at school nearby.

And so you and Brian were the prime song writers?

Hmmmm...(hesitates), yeah we were, yeah. I used to write alot of songs. I mean, I've never found it hard to actually sit down and write a song on the guitar or piano. At that time people like Robert, in fact, weren't writing much of any songs. Kevin was writing songs because he's quite a natural songwriter. But yeah, I think I never found it hard to write a song. I know there's a craft... I never had any sort of block about sitting down and writing a song. I could do it now. If you asked me to sit down at the piano and write a song I'd do it.

OK, go!

I'm not going to.

Alot of those early songs kept popping up, didn't they? Like on Wilde Flowers and on the early Soft Machine?

That's right. Alot of that stuff. I think IŐd never written a song before Wilde Flowers started. I mean, we were doing covers. We were doing all the Beatles stuff, whatever. All the stuff that was... Yardbirds, Kinks. We played all that stuff because that's what there was. Stones, we did some Stones numbers. R&B numbers. And I don't know why, I just started writing stuff. Robert liked trying that... singing them... so, yeah, I never found it hard to write songs.

I asked Robert why he didn't write songs back then and he said that he just didn't have a piano or anything.

Yeah. It's true.

It's interesting that you would write them and he'd just sing them.

It is weird when you think; especially what he developed into. But it's true. Because I'd started on guitar, you've immediately got something you can play a chord on, you know. But because he didn't-- he does play guitar a bit and he plays the piano a bit-- alot-- but that's right, he was living a, kind of, fairly nomad life most of the time. Whereas, I mean, it's like one of those things: most of the time I had at least a part time job. So I had some kind of support. Also, I was living at home, at my parentŐs house, so there was a piano there. It's crazy, things like that, you know.

And you didn't like to sing?

I don't. I have no confidence in my singing voice at all. Brian used to sing-- my brother. I did a few backing vocals on Chuck Berry things.

But, generally, you'd write songs and they'd have lyrics and you would hand them over to Robert or Kevin or whomever?

Yeah, that's right. I mean, a couple of songs I did with Robert. I started a collaboration with him which, in fact, still goes on today. Where I'd write the music and he'd write the words. A couple of things we did with Wilde Flowers that was true. But, yeah, at that time, most of the time, I'd write the words. They were not profound words. You know, just sort of, "Whoa, baby, why have you left me?" with a few decorations.

I think the Wilde Flowers Voiceprint CD is pretty good!

I'm glad it came out. Because those songs, I was happy with them at the time. They're not bad songs. I mean, and it would have been a shame if they hadn't ever appeared.

So what were some of your earliest songs?

Actually, one of the earliest songs I ever wrote was Memories, which was... It's funny it was one the ones that is most covered by other people. And it's probably one of the simplest songs I've ever written, in fact. I think it was about the second thing I ever wrote. You know, it's like B minor, E minor. There's not even a proper bridge to it. It's a very simple song and it works for that reason. People can sing it in different ways. Yeah Robert did a version as the B-side of one of his singles. And it was copied by... did you ever hear the version of Whitney Houston singing it?

Yes, by the band Material! One time only. I couldn't believe it!

If you check it out, Whitney Houston, obviously before she became famous, she was just, like, used as a session singer by (Bill) Laswell. But she actually copies Robert's phrasing on his record-- exactly. Because that's what they gave her. They gave her the record to listen to. She actually copies the same phrasing!

That's not a bad model.

No-- its good!

So you actually get royalties for that song?

Oh yeah! Over the years it's been one of the... obviously I'm never going to make a fortune from it unless they release Whitney Houston's version of it saying "featuring Whitney Houston." But, yeah, its been covered by quite a few people in interesting different versions. A couple singers in Germany called the Rainbirds-- two female singers, a couple female singers, did a very haunting version with simple piano. And Damien and Naomi. I think Galaxy 500 did a version of it.

One of the nicer versions is the one on the Wilde Flowers record that was a demo of your songwriting with Ratledge playing the piano on it...

It's nice isnŐt it? I kind of half-wrote an idea for Mike to play it with, kind of, an Eric Satie feel to it. A very simple, floating thing and he developed it. Because I'm not a keyboard player in that sense. I just gave him an idea of the notes that I thought would sound nice and he worked it out to a more professional sound. But yeah, itŐs a good version of it.

Yeah, and it's nice to hear him play the piano in that sedate way. Don't get me wrong-- I love his organ playing-- but it's nice to hear him playing piano calmly and not freaking out. Which leads us to him freaking out on organ and you on the fuzz bass. What's that all about?

Well, yeah, in fact it was Mike Ratledge's idea that I should use fuzz. Because for the second Soft Machine record-- which is the first one that Iplayed on-- alot of the stuff was written by him. And it's kind of... very constructed. And lots of lines of the bass. And the bass had to be as strong... it wasn't just sort of playing... you couldn't... it had to be a strong melody line or a counterpoint line to something that he was doing on the organ. So it had to be really strong and sustained. So he suggested why didn't I get a fuzz box, as well. Because you get a much more powerful sound with it-- a much more linear sound. So yeah, it was Mike Ratledge's idea, really, that I started playing fuzz.

You played it last night. It's part of your thing now, isn't it?

Yeah, it is. I stopped playing fuzz completely about ten years ago because I was a bit embarrassed. You know, "Hugh Hopper-- doesn't he do anything else but fuzz?" ÉSo many people kept asking me to do it and I started working with Lindsay Cooper's Oh Moscow project.

So tell me about the transition from the Wilde Flowers to you being in the Soft Machine. How the hell did you become the roadie for the Soft Machine?

In fact because I stopped playing. I left Wilde Flowers. I even stopped playing bass in Wilde Flowers. I started playing sax because the band became, more and more, kind of like a soul band. We were playing Tamla-Motown stuff and James Brown stuff, Otis Redding. Because, in fact, thatŐs what we were enjoying doing and it's a little easier to play that kind of stuff. Yeah, it was easier to get gigs but also I was really into it. All of us were all really into that kind of music.

So, anyway, I started playing sax and gave up bass and then I sort of lost interest in the whole thing and I didn't play for a whole year or so. By which time Soft Machine had started with Kevin and Daevid and Robert. So they asked me if I wanted to be a roadie and like a fool I said yes!

Was it foolish or...?

God, yeah. We did... the first tour I did in the States was supporting Hendrix and we did two and a half months non-stop, coast-to-coast and back again and back again. In February of '68, which was very chilly. You know, it's great looking back on it now. But it was hell at the time, you know, because in those days you didn't have giant crews. It was just one guy for Hendrix-- Hendrix's roadie-- and one guy-- which was me-- for Soft Machine. And that was it. In a U-Haul truck.

Just driving from town to town?

Overnight. Maybe getting a couple of hours sleep before the gig. So it was like... you can do those sorts of things when you're young, you know, but I couldn't do it now.

And you didn't even get to be the rock star! You had to be the roadie!

Yeah, that's right, but I got better pay!

Is that right? But I imagine it was a close-knit group.

Yeah, it was. Although the roadies didn't see much of the band because they were flying to gigs and we were driving overnight.

You would go with the Hendrix roadie?

It was just the one truck and the two roadies. We started off sharing equipment and it was disastrous.

So then Kevin couldn't take it and he dropped out?

I did two and a half months. Then they recorded the first record and then they came back again in the summer and did another 3 months tour or something.

I'm sorry, I don't get it. You did two months...

...as a roadie. I had enough after two and a half months. They went on more tours, basically.

So then, how did you end up being asked to be in the band?

Well, yeah, at the end of that year Kevin had enough. In fact they'd all had enough. Robert stayed in the States and did a demo of his stuff. Mike Ratledge didn't want to do anymore. In fact, what they'd overlooked is the fact that they had a contract to do a second record, which the record company insisted they do. So Kevin didn't want to do it and said, "Not interested," so they asked me to do it.

So when you say Robert did a demo, that wasn't when he did the Moon In June stuff was it?

Yes.

So he did that before you'd even done the second Soft Machine Album?

Yeah. In fact he lived out in California at Hendrix's house.

Yeah, he told me about that. And some of those early Wilde Flowers songs ended up in Moon in June?

Yeah. That's right. Alot of the stuff on the second record were, in fact, my tunes with his words... which he'd rewritten the words. Alot of the songs we'd done in the Wilde Flowers, he wrote new words for most of them.

On the Wilde Flowers album there's that song A Certain Kind sung by Richard Sinclair.

Yeah, wonderful isn't it? ItŐs Like a sergeant major in the Army singing it, yeah. (sings in funny voice) "A Certain Kind..."

Right. And that song's one of yours that ended up being on the first or the second Soft Machine record?

That's from the first one. Yeah. There's a couple of my songs on the first one.

So you were a roadie and honorary songwriter. What about that whole Giorgio Gomelsky thing? I guess you weren't in the band then?

He was here last night, Giorgio. We had a drink with him afterwards.

Robert has said so much, just in the last couple years, about the fact that he was kicked out of the Soft Machine. What do you think about that?

Well, it's right, he was kicked out of the Soft Machine. But what's sad about it is that he's becoming more and more bitter about it now. For a long time he just didn't give a shit. I mean, you know, he was annoyed but, OK, that's gone. That's part of something else. But the last couple of years, it's true, in interviews I've read, he's been more and more bitter about it, which is a shame. I mean, it's true, he was kicked out. I mean, well, he was encouraged to leave, you know.

Because you guys were just going in a more intellectual direction?

Well, not intellectual.

How would you characterize it?

Just instrumentally. We were not interested in doing songs and stuff. That's what he wanted to do, yeah.

When you say songs-- you didn't fancy the vocals?

At that time I wasn't at all interested in vocal music... words. Where now I'm more interested. But at that time I was only interested in instrumental sounds.

Do you think you had, in your head, what happened later, more or less? Like, say, on Soft Machine 5?

Well, not that particular record. For me, Third and Fourth Soft Machine records was the kind of stuff I liked doing. Not so much the fifth one. That was kind of... that was more...

Was that the last one you were on?

No, I'm on Six, as well. Because there were so many personnel changes, anyway, after Robert left. Trying different drummers. And Karl Jenkins came in, which was a different influence. For me it became a more of an ordinary kind of band. You know, it was like it didn't have that quirkiness that it had before. Its probably a better musicianship but less, kind of, quirky interest for me.

Yeah, Robert was such a quirky element then. You weren't worried about losing that quality? The Soft Machine definitely lost something then.

Well, I can see that. But, in fact, in the end my feelings against him were much stronger than any logical feeling I might have had about the music, you know. We just weren't getting on. It was like "divorce time," you know? It's a miracle that bands ever stay together. When you think, three or four young males fighting over their territory... their creative territory...

So, as well as the musical differences there was a personality conflict?

In a sense, that was more important than the musical differences because, I think, if you can't get on with someone... It's like in a marriage. You can't logically say whatŐs wrong about it. It just doesn't work. There's no rapport anymore. It's that kind of stuff.

He doesn't seem to be angry so much at you. It's more Ratledge.

Yeah that's right. Because, in a sense, he asked me to join the band and I wasn't one of the first members so it's, kind of, not so deep-standing. Also we've worked together since and we get on OK. We still collaborate on songs. But with Mike it was like, "Boom. Finished." There was no real respect between Mike and Robert, as such. It was, like, Robert felt rejected and Mike wasn't interested.

And now you still collaborate. On Shleep, Was a Friend is one of yours.

In fact, that's quite an old song. I wrote the music of that about... early eighties... about '83, '84. And it's had several different lyrics. And Robert always liked it and thought maybe he'd do something and it never got done. And then he wrote some different lyrics for it quite recently-- about a couple of years ago.

Actually, we did a version of it-- which still exists, which hasn't yet been released-- which was going to be on a compilation. Do you know a record label called Ponk? It used to be Fot Records. They do very irregular, sporadic compilations of different things, with odd tracks that would never see the light of day. I've done a couple of things for them before. And Robert and I did a version of that song. I layed down the tracks in a studio and sent him the tape and he just sang it on his four track and sent the tape back. And it's a nice record. And it should have been out years ago but their latest compilation just ran out of money or something.

And itŐs the words from Shleep?

Yes. It has a slightly different feel to it. It has more of a sustained organ feel rather than on his record he has drumming and bass guitar, something like that...

Yeah. How about what he did with Free Will and Testament? It's a whole different feel...

It's great! Right. That's Kramer's song. Kramer wrote the music. In fact, that was the first collaboration I did with Kramer. That was one of the pieces he came up with in the studio. And I did some bass stuff on it. I just remember saying to Kramer, "This would sound great with Robert's voice, you know." So, in fact, I sent it to Robert when we finished the first, sort of, recording and he just said, "Great," and wrote some words straight away. And it was one of the quickest collaborations I've ever done with him. Within a week he'd sent back a tape with his voice on it, which I sent to Kramer and just like that... it was a really famous way of working.

What was the remark you made that inspired the title, A Remark Hugh Made?

I was trying to work out a title which had both our names in it-- in anagram form. Because "remark" is an anagram for "Kramer" and his first name is Mark as well-- Mark Kramer-- though he never uses it. But I can never get mine because I have such an awkward name. There's no anagram for Hugh. Or Hopper. At least I haven't found one yet.

I'll work on that. So your brother Brian just bagged it at some point? The music I mean?

The thing is, he always had a daytime job. He never actually gave it up and started playing like the rest of us did. He always had a career. So in fact, he's just taken early retirement. So he's just getting back into music. He's always had keyboards at home and stuff like that. He's gotten into MIDI music recently. Sequencers at home, stuff like that. He's getting back into it.

Does he ever wish he were you-- career wise? Or vice versa? Do either of you ever think the other one made the right choice? Do you ever talk about that?

No. I mean, yeah, being a musician is weird. I can't say if I'm going to be starving in six months time. Or in three months time! But, yeah, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages for me.

So you like the choice you've made?

Yeah. I have a free life-- as much as anyone does.

As far as art vs. commercial success, do you feel like, "Fuck acceptance"? Have you, at different times in your life, gone out of your way to be more accepted than others?

Yeah, I think, when you're younger, you're more "Fuck you." It's like, "This is it. This is me." It's like, "If you don't like it, fuck you." Where as now, I'm more mellow. I can say, "OK, yeah, I better make some concessions." But on the other hand, I would never make a record just to make money. I hope all my records are going to make money because I need to live like everyone else. But I'm never going to make a record just to be commercial. I couldn't do it, anyway. I don't have that kind of approach to music. And I don't really want to. For me, if I produce something successful it's because I have a certain voice, myself, you know, a creative voice for writing music or playing bass. And I can work for... practice twenty hours a day and become another good session musician but I don't really want to do that. I don't want to work in a factory, either. For me, doing things for commercial reasons is not what I want to do music for.

Why did you leave the Soft Machine?

Basically, because I wasn't interested in the music they were doing and I wasn't friends with them as people. There was not a reason to stay in there, except for money. That was the only reason I was staying. Laziness. Plus I was getting paid reasonably well for staying in there. I wasn't happy musically, or with the people.

Was that a time when you were making a reasonable amount of money? Or is it better now?

Reasonable. It was more regular. In Soft Machine times I could always say, "I want so much a week," or whatever. Or, "Can I have a couple of thousand to buy a boat?" or something. And I could say that and there was a good chance it'd be no problem. Whereas now, there could be a month where I didn't have any income at all. Or two months, it depends.

Was that because you were on a major label or because Soft Machine had a loyal following?

Yeah, both those things. The two things went together. The Soft Machine, particularly in Europe, was quite a big name. It wasn't as big as the pop groups. But, nonetheless, it was a living. It was reasonable.

In the 70's there wasn't much going on and you guys definitely had a good reputation.

Yeah, that's right. And on CBS Records it sold OK. But with all that I'm actually much happier now-- just scrambling around for things and doing weird things here and there and maybe not anything for six months. With Soft Machine I could've told you what I was doing for 18 months. All the dates were there. I mean, it's nice for the money. On the other hand, I became very... I lost interest in the music because it was like a job, really, a job doing something else. Where as now I get a chance to come to New York. And next week I could be doing a gig in Canterbury. Someone could ask me to do a gig in a pub in Canterbury.

And Brainville... Kramer made that happen because he'd worked with both you and Daevid separately?

Yeah, that's right. Daevid worked with Kramer before I'd worked with Kramer. Yeah, I've done two records with Kramer and a couple of live things and yeah.

Tell me about your album 1984. When it came out I was young and baffled by it but now I have a greater appreciation for it.

Then you can tell me. I've been wondering myself!

Well, I mean the context. At the time Soft Machine was already pushing the limits of what I could fathom.

Strangely enough, 1984 was really stuff I'd been doing well before Soft Machine. It was really the stuff I'd been doing working with Daevid before all that stuff, when I was still in a, kind of, avant garde period-- before Wilde Flowers, before Soft Machine. Working with loops and stuff like that. Tape loops and cutting up sound collage, that kind of stuff. But I, sort of, messed around with that stuff when I worked with Daevid and also later on, at home, just cutting up pieces of tape, sticking them together and running them-- stuff like that. And then it was the first chance I'd really had enough money and studio time to get to go into a studio. And just record it in a big studio, in good conditions, where I had the time to do it with proper machines.

Did you bring homemade tapes or...

Mostly not....

...or did you make them there?

Yeah, in fact, we even did some big 16-track tapes looping with a big two inch...16(-track) machines, making loops which... you're not supposed to do that. It's against the sound engineer's golden rules. But we did all that stuff. Also, I suppose, it was a kind of reaction against Soft Machine because I was starting to get bored with Soft Machine-- not happy-- and wanted to do some stuff differently from being in the band.

And when was that? Were you still in the band?

Yeah. No, I actually started working on it the year before I left. So it was, yeah, '72.

So were you thinking Stockhausen? Terry Reilly or that sort of thing?

Those are two good names, certainly. Certainly Terry Reilly. I mean, that was a big influence. And there was a couple of pieces of Stockhausen. There was one called Kontakte which is.... now you could do it in, like, 5 minutes on the computer. But then it was... you'd be sitting in a studio for months getting all this stuff down. Treating, electronically, stuff, which now, you could do with an effects box on stage.

And what about the whole Dada angle?

I've got it now. I didn't, at all, get involved with it, at all. There were people on the outskirts of Soft Machine who were very into that but it...

Who are you thinking of? What types of people?

Actually, people who were really Soft Machine fans, but were not part of the music world. They were, kind of, part of the art world or poets or artists or critics or, kind of, writers.

You mean, like those Pataphysical guys?

Yeah. All that stuff. I forget the guy's name. There was a guy in London who was the official Pataphysical Chairman of Britain. I forget his name. Oh god.

They had a whole organization, right?

That's it, yeah. And we were the official orchestra of the Pataphysical Society of Great Britain. But it was one of those things. It was fun. It's part of Surrealism and Dadaism and stuff of the thirties. I mean, it was very hard to tie down what it means. If you ask someone what Dada. means, it's just the art of the ridiculous or something... or the art of... give it some crazy definition. But it was really, kind of, a rebellion against logic and, kind of, being straight-- the straight world, really.

On the one hand, the tape loop has a dada connection but so does Robert's whimsical singing.

I think Dada is like one of these loose terms everyone has their own definition of...

The art of the absurd. Or making art out of every day life...

I think, mainly, it was a desire not to be part of the mainstream of art or of life. Do something ridiculous because life is ridiculous. Therefore you shouldn't do serious things. Or if you do serious things, you should do it in a weird way that's going to surprise people. Which is great. But, for me, it's not a clear philosophy. It's, sort of, an approach to other things rather than a clear thing in itself. But, then, that's because I was never particularly involved with it. It's something I saw from the outside.

I stayed a fan of the Softs though the seventh album. But it seems to me, when Robert left, that's part of what ended: that whimsical thing. The music became very serious after that.

That's right. Well, Mike Ratledge was always very serious about music. Unfortunately, he never really enjoyed playing live. He hadn't really enjoyed being on stage. It wasn't his life. He really was much happier composing stuff-- which he was very good at doing-- or arranging stuff or working at home. He didn't ever really enjoy being a touring musician.

Did you enjoy it?

I enjoy it now more than I did then because I have more freedom in my life to do what I want to do. At that time I was rather... also you get mellow with age. You see what the good things are and you avoid the bad things. Whereas when you're younger, you go head first into everything and you want everything just to be what you want.

Did you ever tour with the Soft Machine in the US? The three of you guys?

We did a couple of things in the States but mostly in Europe. Well, actually we didn't do it as a trio. Yeah, we did it with a quartet. With Elton Dean in '71, I think, was the first time we went back. We were supposed to do... we were with CBS Records and we had a lot of work with the jazz festival circuit. We were following Miles Davis everywhere. I saw so many Miles Davis gigs in those days... '71, '72.

How did you feel about that?

It was great. I loved that music at the time. I like the electric bands of Miles.

So now you and Daevid are together in Brainville.

I think it was KramerŐs idea, really. I think Kramer had an idea for doing a record or a tour. An idea to tour with Daevid and me. First of all, it was going to be David Licht, a drummer who he'd worked with before. But David couldn't do it so we asked Pip. We were supposed to go to Israel and had some gigs in Europe but it's been very hard this year. Things seem to have been cancelled left, right and center for different reasons. But this is the first time we worked together-- in New York-- first time.

And this was the first time you'd been together musically with Daevid since the Daevid Allen Trio in 1963?

That's right. We did five gigs in England in June just as a trio because Kramer didn't come over. But before that I hadn't worked since... what?...1963 with Daevid. How long is that? That's 35 years!

But it's been fun?

ItŐs been great. The five gigs we did in England as a trio were great. It was really nice. I can always work with Pip. It's never a problem. We've done so many gigs together over the years. I know we can get on together, especially improvising. But I really didn't know how we were going to get on with Daevid. Because Pip has worked with Daevid in Gong and they've been together and they've been apart and they've had problems and they've been together. But it really worked out well. We all enjoyed it. I think it was creative. It was improvised with a few songs. Stuff like that. Basically what you heard last night. That kind of approach.

Why did you decide to do Hope for Happiness? That was surprising.

I think that was Daevid's idea, actually. In fact, itŐs my brother's song. Brian wrote that. I can't remember how it came about. I think somebody suggested it. So we tried it and it's a good, open vehicle to do things on, you know.

What songs do you think you'll play for this Wyatt tribute?

We've had a look at Sea Song and The Last Straw from Rock Bottom. And a couple of the ones off the new record Shleep. There's one called Heaps of Sheeps. We might try that also there's one I co-wrote called Was A Friend-- the one we were talking about before. And plus Kramer's Free Will and Testament. Oh and Memories!! We might do Memories again.

It's got that kind of schmaltzy, nostalgic feel.

Everybody take to the dance floor!

You played on Alifib didn't you? That was quite an opus, huh?

Yeah, it was great. In fact, Robert had already recorded his piano part and I think it was like a tape loop rhythm part on that and Gary Window had recorded sax on it. Then they sent a demo to me to see if I could come up with some sort of bass line afterwards or whatever-- which I did at home. Then we went into the studio to record it. So, yeah, I really liked it. I was pleased with that, also, because it was a reconciliation with Robert. It was the first thing we did together after he'd left Soft Machine-- a year later.

(Joking, as Pip Pyle walks by) Can you shed some light on the whole Pip and Robert Wyatt wife-swapping controversy? Was that a coincidence?

Nothing is a coincidence. By chance, Alfie was Pip's girlfriend at one point. And Pip's ex-wife was also RobertŐs ex-wife.

Girlfriends seem to play a large role in all of this. Kevin used to go out with Pye Hastings late sister?

That's how we met Pye Hastings, because he was Kevin's girlfriend's much younger brother. He was a 15 year-old schoolboy when we first met him. That's right.

And what about Caravan? You didn't overlap much with them?

Well, I did really. Because that came from Wilde Flowers, as well, and yeah, they were really the more melodic pop song... or poppier songs from Wilde Flowers and they developed that side of it. Pye is a very good song writer, a very natural song writer. He says, himself, he doesn't consider himself to be a great guitarist. But he plays guitar well for what he wants to do. It fits well with his music. He's not interested in being a jazz musician or in a fancy conservatory. He doesn't do that.

That must have been difficult to reconcile with Robert after his accident. Were you still on the outs with him?

No, we'd made up by then. It was a shock. I remember I heard it from Gary Window, I think. Yeah, Gary phoned me up and told me about Robert. I think at the time I didn't see that he'd be able to handle it. I'd never thought of him as being a particularly strong person to be able to handle a thing like that. I thought it could be easy to try and take his own life because he couldn't stand the idea of being in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Which certainly would have occurred to me, you know. You can't tell until it happens what you would feel like. But he handles it OK.

If I call Robert or Robert calls me, I mean, I just don't think about it, really. He was never a sporty person. He never went sailing or he never went hiking. Although he's lost the ability to play a drum set--he can't play the bottom half of a drum set-- he would laugh at the idea of going jogging, for instance. So for him, most of his life was actually sitting at home and having cups of tea, anyway. In fact sometimes I have to remind myself that he is in a wheelchair. But then that's because I don't see him very much.

Do you think his music has changed since then?

Yeah it has. Well, he certainly hasn't switched off because of it.

What about, drums versus singing, and doing them at the same time. Was that a factor when he left the band?

It was all part of it. In fact, as I was saying before, it's all because we just weren't getting on as people. If he'd been the greatest drummer in the world or the greatest singer in the world, if you're not getting on with someone then it just doesn't help. You can't say, "I must get on with this person because he's the greatest drummer in the world." It just doesn't work. You can't even tie it down to those logical things. You just don't get on with someone so you just hate their face. They walk in the door and you think "I wish you'd go away," or something. It's like any other relationship. Since you've got to play together it makes it twice as bad.

Do you have a family?

Yeah, Several! One daughter of 19 and another one of 2 1/2 from two different mothers.

How's your daughter of 19?

She's actually started playing bass about three years ago but then she's given up now. She's into music but doesn't really have that kind of neurotic desire that you need to have to really get involved in an instrument. But she's always been into music.

How about that neurotic thing? Tell me about your own neurotic relationship to the music. Do you agonize over your recordings or do you have a more laizze fair attitude?

IŐm more laizze fair than I used to be. Because I know now what I can do and I know what I can do easily and I know what it's going to be hard for me to do and I accept those problems. I mean, I can now trust myself. If it's someone I'd never met... then I'd say "Yeah, sure," and it wouldn't worry me. I might think, if they presented me with this chart that was really horrendous-- and I'm not a particularly good reader-- so I'd have trouble with that. I know I can do certain things if people ask me to do them and I know I can do them well. I can contribute to a project. So it's not a problem anymore. Whereas when you're younger, you have alot more bullshit about you. You think, "Ah! I can do this." and if can't do it, if you're proven wrong, then things get nasty. Whereas now I can see that it's no problem for me to admit that I can't do something so it makes me more relaxed. So I can probably do things better than I could've done before.

Did reading ever become a problem after Robert left Soft Machine? That horn section you played with was pretty serious wasn't it?

Yeah. It wasn't a problem for reading in that band because the bass lines were mostly riffs anyway.

Did you ever feel a conflict between a more academic approach vs the Chuck Berry School?

Not really. Not at that stage, anyway, because it wasn't that academic. The whole thing about Soft Machine, when I left it, it was becoming kind of a jazz-rock funky thing, which I love-- played by the right people. But I, for one, was not the right bass player for that kind of stuff. And then, in my opinion, they weren't the right writers and other players for it. They all had a lot of qualities but that wasn't one of them. Certain people dearly want to be black, you know. And then they weren't black players and whatever that means. Or they wanted to come from Harlem. I never have come from Harlem, and I know what I can do. I love some of that stuff. I love a lot of it but I don't necessarily want to play it myself.

You did that recent CD Spaced, right?

That's right. That was kind of... Alot of that was just the same kind of approach as 1984-- working with tapes and recording stuff live and then cutting it up. Making loops of it, overlaying things. I did a little bit of that on the beginning of one of the tracks on Soft Machine Third-- Facelift-- which has some live stuff mixed with studio stuff. The Spaced project we did it, actually, for a show in London which had dancers and acrobats and they asked us to do the music for it. So we did this tape and it's recently come out on Cuneiform.

Did you have something to do with remixing it?

In fact, thereŐs a guy called Mike King from Canada who tracked down where the tapes were. The engineer who recorded it for us went to live in the States and he's now a bicycle repairman in Connecticut--great! He had it in his loft or something. In these boxes of tapes.

What about the Wilde Flowers tapes? Didn't Mike (King) get those from your brother?

Yeah Brian had alot of them. We had them on acetates; on vinyl demos because thatŐs how you had them in those days. ItŐs like a seven inch EP. ???Étracks on there. That's why its scratchy sounding.

I don't think they're bad, considering...

They've been cleaned up. That was Brian's project-- my brother. He got that going. In fact Voiceprint's going to put out a further, even earlier, archive project of stuff. Like I was telling you about my brother and I singing Chuck Berry songsÉ more interesting early stuff with Robert and Mike Ratledge. Kind of playing free jazz around the time of the Daevid Allen Trio. We used to get together in each other's homes and pretend to be John Coltrane and things like that.

You guys always have a kind of self-effacing attitude about jazz. It seems to be something you all share that survives from those early days...

We've always got a, sort of, interiority complex about being real jazz musicians, thatŐs right.

Was it because you were young guys in England?

Yeah, young white guys. And also speaking for myself, I never really studied jazz technique and jazz harmony and all that stuff you really want to go into. I just played by ear I'm really kind of a rocker with jazz tinges. As well as other things. I have other interests as well.

What do you think of when I mention Mark Boyle ?

Mark has become quite successful because he's, kind of, been taken up by the art world in London. He did all the light shows for Soft Machine. He does paintings. He's really become quite successful.

Do you see him still?

I haven't seen him for about 20 years.

I saw him in 1980 or so. He did a show in California and played some Softs tapes and talked about the light shows.

Even when I was in the band he came along and did a few special shows for us as well. He gave Mike, Robert and me one of his pictures. He had this project to throw darts at an atlas of the world and wherever the dart landed he would go there and make this epicoat casting.

Yeah, that's what was in the show I saw. It was amazing. So he gave you one of those?

Yeah. Mine is actually a part of the coast of England, the south coast of England-- sand at low tide. You know how sand goes all... kind of... you can see the shape of the wave, the ripples. You can see shells and stuff in it.

And he wasn't involved with Spaced?

He wasn't, actually, although it was pretty much composed by the same family... I forgot the guy's name. It was his show really and he put it together.

Who was Ted Bing?

Ted was a school friend. He got into photography. He used to take photographs of everyone. He's now living in Norway-- lives like a Viking! He's about 6 foot 6 anyway. Now, having lived in Norway for the last 20 years, he really looks like a Viking.

You guys always had a multi-media aspect to the Soft Machine.

Yeah, we did. Daevid was very important in that he encouraged... he was the instigator of some of those things. He would get Ted to take a picture of him-- real kind of freaky pictures-- and then project them on him while he was playing and reading poetry and stuff like that.

Well thank you, Hugh. I'm sure there's more I'd like to know but that about does it for now.

Thank you, Mark.

© Copyright Mark Bloch, 1998, www.panmodern.com