Send $50 cash money or check to Mark Bloch c/o The Word Strike Action Committee PO Box 1500 New York, NY 10009 for your copy of this 32 page institutional critique of the art world, poignant and funny polemical treatise and important collector's item.

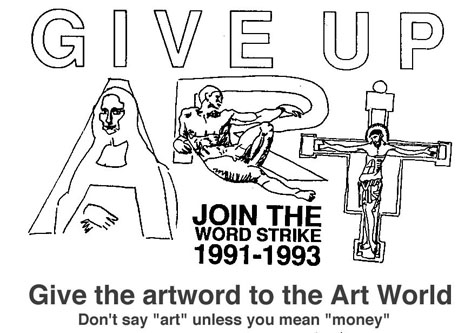

JOIN THE

WORD STRIKE (1991-2001)

Don't Say "Art" Unless You Mean "Money"

"GIVE THE ART WORD TO THE ART WORLD"

We must give the word "art" to the art world. Businessmen can become artists now, its what they've always wanted. Artists can become businessmen now, it's what they have always wanted. Instead of just saying everyone is an artist, let's make it true. Let's change the meaning of the word art to mean business. And everyone who is buying and selling. We are all artists when we deal with money. Meanwhile there are the stupid few who insist on not being artists. What would those people do? What would their activities consist of? They couldn't hide behind a grandiose term like art anymore so they'd have to use more specific names for what they do like paintings, dances, songs, brain-teasers, books, poetry, plays, stories, drawings, sculptures, etc. And if not for money why would these people do these things? Probably the reason would be difficult to explain. Maybe it's better not to explain. Not to give it a name, just to do it.

If we give the art word to the art world that will leave a void and the things people fill that void with can be clear and honest and fresh and come from a place inside each of us that exists before the words to describe it do. Words are just symbols and pictures are just symbols but what are they symbols of? Concepts? Things? Whatever it is those symbols represent, let's use that to understand what the symbols do and how they work and look at what they've created for us thus far. Yeah, we can let the void be filled with the same old stuff we filled it with when it was called art or we can give that stuff to the art world as a gift. The art word, the history, the museums, the galleries, of course the artists, the masterpieces, the stereotypes, the jealousies, the judgements.

We can give all that to the art world and instead try filling the void with something we all want: the understanding of what history is and what words are, the understanding of what is really happening to us when we are moved to call something a masterpiece, the understanding of the reasons we use stereotypes, and discovering the reality behind the myths, (of course reality is a problematic word, too), the understanding of jealousies and the abandonment of the fear that causes them, the understanding of our judgements and the criteria we use to judge things, and where that comes from. Yeah, if we fill the void with these things and that same time try to keep it fresh and honest and flexible enough not to get bogged down by new words and dogmas perhaps it would be an experiment worth trying. So I say give the art word to the art world , let it denote only activities involving money and let your attention drift effortlessly to the void created by its absense. So don't say "art", don't say anything . During your free time, feel free to send a clear message to the Word Strike Action Committee PO Box 1500 New York NY 10009 USA.

From a review in Photo Static magazine:

The Last Word (Panmag #28) by Mark Bloch. 30pp– half letter–xerox. P.O. Box 1500, New York NY 10009 — This booklet, comprising thirty pages of diatribe about “Art Strike, Word Strike, Plagiarism and Originality”, mostly serves as Mark Bloch’s account of what went on at the Glasgow Festival Of Plagiarism, which was held at the Transmission Gallery in August, 1989. In addition, he speaks about what artists need to do change the world, and occasionally his vision is quite clear and his voice strong. Among other things, he suggests that networkers need to “control” the way the mainstream media presents us.

The point is well taken; much of the outside coverage I’ve ever seen concerning “Networking” is embarrassingly trivializing and shallow.

Bloch, unfortunately, is not much of a reporter. At his best, he records many details of the event, which I neglected to include in my own account [see pS #38], and which add a certain understanding of what went on. More often however, the ideas and incidents he recounts are misrepresented, skewed by Bloch’s defensive attitude, as evidenced by the following passage: “I’m tired of smug attacks on anything passionate and spiritual. Stewart [Home]’s wordy diatribes, admittedly entertaining when taken with a grain of salt, often seem designed for masses of robots or tractors, not human beings.…” Often, this defensive posture gets in the way of what he is trying to say. And it makes a lot of his comments seem snide and hostile.

The most valid thing Bloch does in this booklet is call into question the Festival of Plagiarism itself, the reasons for having one, and the way that it was organized. He goes a considerable distance toward answering a lot of these questions for himself, but what about us? Are we to take Bloch’s word as final, as his title demands? Not hardly. If the “success” of the Festival can be gauged, I for one feel that its most significant contribution is the questions it begs; and by rejecting the entrenched, the orthodox, and the dogmatic, it requires us to come up with our own points of view, and calls on us to rigorously field-test them.

Bloch’s booklet is therefore a part of a fitting epilogue to what was intended to be a set of concerted challenges to conventional ways of thinking about cultural output, but it does not go far enough. It asks us merely to see things Bloch’s way. And the last thing the world needs is another person wanting to lead us to a mythical “truth”.