An

Authentik and Historikal Discourse By Mark Bloch

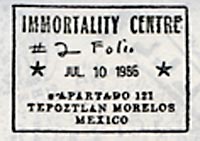

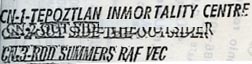

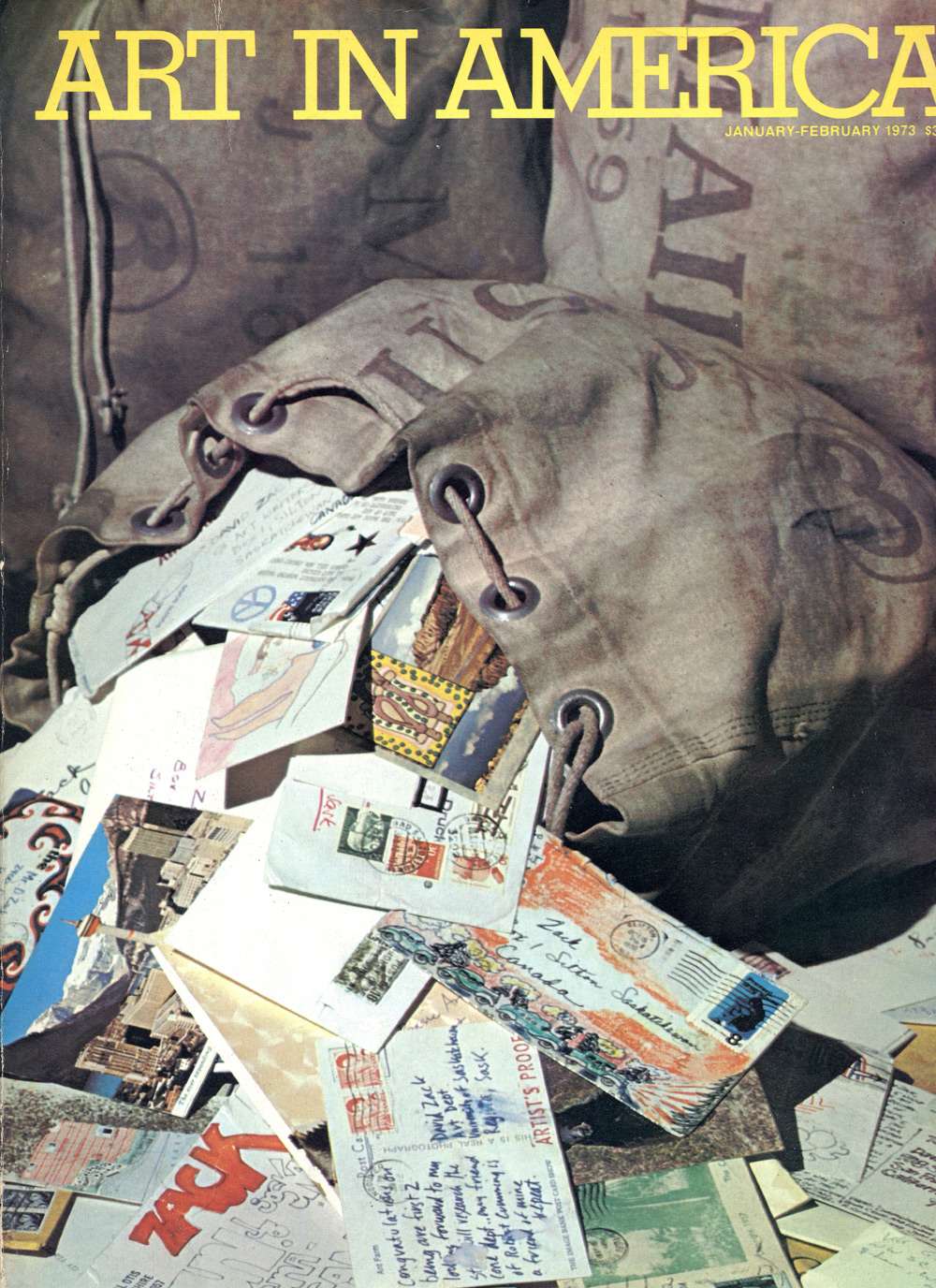

This is a chapter reprinted from Amazing Letters: The life and Art of David Zack. edited by Istvan Kantor for The New Gallery Press, contact them for ordering and further details. About five years ago, while attending a very swanky art world party on the upper east side of Manhattan, I was introduced to a well-connected Mexican gallery owner. Now here was a great opportunity to advance my own art career. During a lull in our conversation, in an attempt to keep things moving, I casually mentioned that I knew a Mexican artist that I doubted that he would be familiar with. “Who is that?,” he asked, charmed, completely engaged and genuinely interested. When I replied with the name of the notorious mail art legend and my late colleague, “David Zack,” this man’s countenance darkened and his expression turned to one of complete revulsion. He did not even attempt to conceal a horrified reaction, not just on his face, but exploding from the totality of his body language. I cannot recall what happened next; only that I never had a decent conversation with that man again. “Your loss is my gain,” said Dr. Al “Blaster” Ackerman, then of San Antonio, Texas, one time as it was confirmed that Zack was on his way from his house to visit me in New York by Greyhound bus. I say “confirmed” because Zack could change his mind countless times and any number of other caveats could enter into the equation to interrupt any Zackian departure. I wasn’t sure what Blaster meant but it was clear by the time Zack got on an Amtrak train to Rhinebeck, NY a month later. I knew all too well that Judith Conaway’s loss was my gain as I gleefully waved goodbye to Dave from the platform at Penn Station. I was exhausted and frankly couldn’t wait to see him pull out of Manhattan. Once I did, I returned wistfully to the wreckage that was my apartment in the aftermath of his visit, but it would be days before I would discover hidden treasures like the fact that most of my beloved record albums and their cardboard covers were stuck together as one giant sticky lump as the result of In the early 1980’s postal artists got to meeting each other in a sub-movement called Tourism, where the idea was to meet other networkers face to face. This culminated around the time of that Zack visit--1986-- the year of the International Decentralized Mail Art Congress, where meetings of two or more mail artists was considered a Congress and larger groups tackled the issues of the day in roundtable discussions. From my Stanton Street apartment, Zack and I took temporary road trips together-- to the aforementioned Conaway's home upstate; to sojourn with the mail artists Cracker Jack Kid, Ben Xona Banville and Steve Random in Greenfield, Massachusetts and other places long forgotten but I must have it written down somewhere. We also must have met with other local New Yorkers of that time-- David Cole, Carlo Pittore, John Evans, Buster Cleveland and Ed Higgins-- but I recall none of it, only the constant turmoil of trying to pry Zack from my typewriter or refrigerator while being lured, as if by extraterrestrial forces, to be an accomplice to his appetite for both. Together we created an issue of my Panmag for which he wrote, among other things, a poem about my neighborhood, I must admit that Zack, peppering his sentences with Spanish like he did with the letters and recordings that preceded him, fit in well in my Lower East Side neighborhood. He was adaptable. Before his move to Mexico, David lived in Canada, where he was rumored to have burned his house down, and Los Angeles, where I first met him. I first heard of him when I read a major article on mail art he wrote from Saskatchewan in the early 1973 issue of Art in America: An Authentik and Historikal Discourse on the Phenomenon of Mail Art. In addition to a long discussion of mail art in which he drops the names of most of the important networkers of that time, Zack also mentions corresponding with fifteen or sixteen “Nut artists,” whose ranks included Dave Gilhooly and Roy DeForest. The Nuts were an important development in the life of Zack and his article was a watershed moment in the history of mail art because, via a mainstream publication, it reached beyond the few who it had swayed through word of mouth. Now Zack’s typewriter-as-mouth discourse and an article in Rolling Stone #107 (April David Zack’s article established him historically in a key position as a documenter-participant during this important juncture between the first two major periods of the network of that time: the not pre-meditated, ever-expanding-but-closed “in crowd” that characterized the practitioners of the overlapping activity in those days: the small Canadian network plus Johnson’s mostly New York-based Correspondence School plus Fluxus (as well as the untidy and scattered aftermath of all three) AND the very beginnings of “Mail Art” as an international, democratic, quasi-movement, now called “Mail Art” that for the next two-plus decades, emanated outward toward the pre-hipster masses, engulfing both the art school-influenced crowd in the United States and the underground-by-necessity networks living under a spectrum of repressive regimes in Eastern Europe, South America and beyond. Zack’s article was one of a small handful of texts of that period that spun the term “mail art” into widespread use. In 1972, before Zack’s article but as an indicator of the Zeitgeist, Ray Johnson, founder of the activity in the form of the New York Correspondence School, wrote an obituary for the New York Times and subsequently sent it out as a mailing, saying his School was a goose that “died this afternoon before sunset on a beach…It just wanted to be alone to die without a human standing there talking to it. I felt so bad. So it flew off and soon I was aware I couldn't see it anymore.” On many occasions I asked Ray about Zack and it was clear Ray did not want to talk about him. Perhaps it was the article, in which he was called by Zack “the meanest man in America;” perhaps it was something else, but their relationship had ended well before I encountered Ray in 1983. “Postal Art,” “Mail Art,” “Correspondence Art,” “The Network” and the “Eternal Network” are five names for the same indefinable thing. There are others. The names refer to an international network of artists, non-artists and anti- artists that exchange work through the international postal system. In the mid-80s Zack, Carlo Pittore and a few others tried to rename it the Entity or N-tity or N-“Titty” and while it never caught on, it may have represented a second Golden Age of the activity. Like the present post-Internet Nine Thousandth Golden Age of Mailed Art, the N-tity had its roots in Ray Johnson’s loose-knit group of correspondents that blossomed in the late1950s. By the late 60’s and 70’s the early adapters in art schools and universities were on board, the various networks—some political, some arty--connected with each other, converging to create what the late Fluxus artist Robert Filliou coined the Eternal Network. He meant something else, but in some quarters the name has stuck. By the mid-1990s, the Network connected some 50 plus countries. It was estimated then that some 50,000 artists had participated but the actual number can never be known due to postal art’s elusive qualities that are a result of its openness. Like the Internet that followed it, there are no formal parameters to the Network; it is still open to everyone who wants to participate. That participant need not be an artist or make art. The Eternal Network is not for sale- it is a living model for an alternative system with a goal of international cooperation. Because this democratic process accounts for an uneven “quality” of exchange, mail art is sometim The Mexico years were the ones during which Zack established the CN or Correspondence Novel, an important theoretical construct. Zack shuffled all of his correspondents into one of the nine CNs. Each of the groups had a number and half were named for obscure personalities or concepts, such as the one I was placed in, “CN8 Ezmeralda,” CN-1: Tepoztlan Immortality Centre (also known as “the International Mexican Art Magazine.” Zack told Pete Horobin it was “about making a home.”), CN-2: Outside the Outsider (for the partic

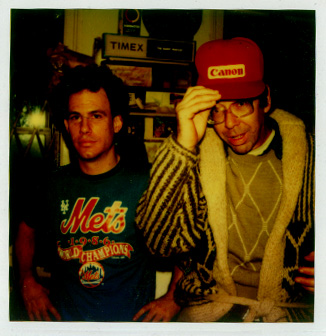

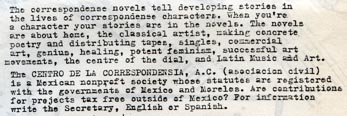

Zack would adorn each letter with one of the rubber stamps he had made to commemorate the individual CNs. Eventually he made color covers for each one. I know this because I began to inquire about what the concept was all about and he sent me a photo of them all laid out on the floor arranged in a grid. As with most questions one asked Zack, especially by mail, I never quite got a clear answer of what the uber-plan was or why one person was in one and not categorized elsewhere. In fact, after a recent re-reading, I am struck by the similarity between the stream of consciousness prose in his Art in America article, his letters to me and my general perception of him now that he has been dead for as many years as I knew him. Bucky Fuller once wrote a book called I Seem To Be A Verb and this human attribute seems particularly apt in Zack's case. Information flowed through him, around him, under his feet and hands and occasionally over his head, but it flowed and he was an active conduit, embellishing each wave with the little awkward drawings of cartoony faces in profile, bulbous lettering and copies of other bits and pieces of correspondence--both his and other people’s. The genius of Zack seems to be that he ever conceived the CN, a catch-all receptacle to manifest these elusive in-coming and out-going meanderings of those last few pre-Internet years. Thus was Zack's place and position established in the network in the 1980s, as a flawed and imperfect checkpoint for the swirl of activity that surrounded him. It is important to remember that Zack’s contribution was primarily literary. Cranking out his own writing since college, in addition to deconstructing art criticism with the folksy, outsider style one sees in his Art in America article, he was fascinated with everything from pulp fiction (like his prolific pals Ackerman and Jack Saunders), to the post-Dada cut-up method of Brion Gysin and William Burroughs, to the fanciful autobiographical narratives of Henry Miller that seamlessly weaved together the lives of friends, lovers and his own psyche. While Zack’s life was a performance piece, he had an aversion to being on stage. While his life was dedicated to art, his primitive doodles reflected an unapologetic rejection of the skill set that had dominated the concerns of the academically-trained visual artist before the mid-20th Century. Zack’s CN project was the right vehicle to reconcile the pluralism and appropriation of the 80s with the interface between the post-punk performance and audio-visual real time diary that was mail art—all in an idiom that hearkened back to Walt Whitman and William Blake. In a 1986 cover sheet for a ”folio” of excerpts from the CNs, Zack defined the concept this way: “The correspondence novels tell developing stories in the lives of correspondense (sic) characters. When you’re a character your stories are in the novels. The novels are about home, the classical artist, making concrete poetry and distributing tapes, singles, commercial art, genius, healing, potent feminism, successful art movements, the centre of the dial, and Latin Music and Art.” Meanwhile, Zack’s political contribution was that he was anarchistic. His very existence was an advertisement for chaos, randomness and letting chance in as an organizing principle. His allegiance was only to Dada. He believed in it as both political party and religion and demonstrated this in his reverent acceptance of everything that came in and went out as some form of Net Nut Truth. The correspondence work and mail art that Zack sent-- long rambling, sometimes incoherent letters, tapes, drawings, snapshots and photocopies-- stood in sharp contrast to the more pithy postcards and single Xeroxed sheets with strategically-placed rubberstamps and neat, clever slogans that others would send at that time. To receive a piece of mail-art from Zack was to be bombarded by an energetic cloud of messy epistolary frenzy stuffed into an envelope and overflowing into your life. It was often difficult-- literally-- to stuff the contents back into the place from which they had emerged. At the same time, Zack’s gonzo style had some similarities to the cool Ray Johnson School from which it had indirectly emerged: his missives also took the form of letters, actual correspondence rather than conceptual art pieces transported by post. Although taken to new extremes, Zack, like Ray, also had a penchant for including previous epistles among the new ones. It was not unusual to get a letter written to you, accompanied by one to someone else. You were forced to imagine that somewhere else on the planet, someone else was receiving THIS letter he had apparently NOT meant for your eyes ONLY as well as fragments of YOUR letter to him either in the form of an original or a copy, being sent to someone else, all to create another Zackian correspondence cloud. Ray’s quiet concept of the Add to and send to someone else was practiced with evangelical fervor by Zack. One had the feeling he was spinning on a giant turntable at 78 RPMs and just endlessly recycling other people’s letters. Speaking of turntables, even though I am one of the few people to bring Zack with me into a professional recording studio to play cello on several songs, I truly believe Zack’s self-made cassette tapes were an important force to be reckoned with. He paid homage to low fidelity with every 60 or 90 minute recording, playing the cello and guitar and singing ballads of mail art personages over them that would go on for entire sides while recycling older tapes by just re-recording already lousy sound back into a tiny mike. The opposite of slick, the overriding aesthetic sense that one got from both his tapes and his letters was “home-made.” Zack found a way to elevate crude production value to an institutional level. This institution, despite hiding behind the likes of the Immortality Center or the CN or the Nut Art or “Neo Nooze” that preceded the CN, was the barely-organized chaos of Zack himself- a work already in progress. I was introduced to Zack by our mutual correspondent Jerry Dreva in 1980 at the Zero Zero Club in Los Angeles when all three of us were snow belt transplants to Southern California-- Dreva and I from Wisconsin and Cleveland respectively-- and Zack from Canada… I THINK. I was never clear WHERE Zack was from. He seemed constantly in motion during that time and the years that followed but his home base eventually became the ramshackle compound he called the Immortality Center in Tepoztlan, Morelos, Mexico. It was there that I exchanged dozens of very fat letters with him and his live-in goddess, the talented Brit muralist Sno White Jung. But the whole thing began at the trendy club on Hollywood Boulevard with him yelling over the din of the music, that he had started Neoism and the concept of the “open pop star” that anyone can become by changing their name to “Monty Cantsin.” Proposing bouts of boxing with saxophones between me and Monty and then me and someone called Wayzata, and then with me proposing a contest between him and one of my M’bwebwe friends from Ohio and New York who was coming to visit, Zack explained during those very first meetings that the Open Pop Star concept, as he conceived it, is that many people will do the work of the Open Pop Star, use one name that combined the Hungarian Istvan Kantor and the Canadian Maris Kundzins and be a collective genius. I regret we never did commit to the sax pugilism or that I never even had a clue what the hell he was saying, but today, twenty eight years since we met in Hollywood, if YOU do art as some kind of Open Pop Star as Monty Cantsin or Karen Eliot or Luther Blisset, know you will be contributing to an ever-expanding participatory David Zack concept. But why did Zack have to die in the Morelos State Penitentiary in Mexico or some place like it, you ask? David “OZ” Zack’s parents retired in Mexico. In 1981, in his mid 40s, Zack went to live with them. Eventually both of them passed away. Zack slowly turned the place into a conceptual Mailart Merzbau and dreamed of building an amphitheater. He kept cashing his parents’ American Social Security checks long after his folks expired. Eventually Zack was arrested and ended up in jail--either for that or something else. Dying either in prison or not, either in Mexico or Texas, either circa 1993 or 95 and all while using the name David Zack Hill… or David Nazario. Uncertainty surrounds those last years. I got a postcard or two from him but I don’t have them handy. I seem to remember he married someone in jail and there had been amputations. As Dave used to say, “Hmm So getting back to the Mexican gallerist who did not appreciate my uttering the unspeakable name of "David Zack" out loud, yes, that story of the swanky art party, like all Zack stories, was memorable, humorous and perhaps telling… but not an isolated incident. What was it about Zack that brought up such contempt in this man and has been known to do so in others? Why does the mere mention of Zack’s name set off mental alarms-- even in people immune to the idiosyncrasies of the mail art movement? It is not as if the well-heeled gallerist was reacting to the words “mail art” which I did not even have a chance to mention to him. Our conversation was over long before that. But if I needed a backup, the phrase “mail art” itself has been known to be a stimulus that can elicit dirty looks from art world professionals… after all, it was once referred to as the Special Olympics of the art world. So, when hob-knobbing with Art World Big Shots, remember: the words “mail art” are not the only available path to calling forth horror, winces or embarrassed giggles in your pursuit of a torpedoed career. It is good for the initiated (which now includes you) to know that even a passing mention of David Zack carries with it a special stigma all its own.

|

Zack apparently dropping a glass of orange juice on them one day. I did not know that the mishap had happened and probably neither did he, although I wouldn’t put it past him to curiously “forget” to tell me. But Zack was not a malicious character, merely painfully unaware of his calamitous effect on the world. David Zack was as blind and as destructive as the American cartoon character Mr. Magoo, leaving chaos in his wake wherever he went, a diabetic like his parents since his teenage years, with his limited vision getting worse as the years passed and with that as just the start of his problems.

Zack apparently dropping a glass of orange juice on them one day. I did not know that the mishap had happened and probably neither did he, although I wouldn’t put it past him to curiously “forget” to tell me. But Zack was not a malicious character, merely painfully unaware of his calamitous effect on the world. David Zack was as blind and as destructive as the American cartoon character Mr. Magoo, leaving chaos in his wake wherever he went, a diabetic like his parents since his teenage years, with his limited vision getting worse as the years passed and with that as just the start of his problems.  27, 1972) by Thomas Albright were blasting the secret knowledge to baby boomers everywhere.

27, 1972) by Thomas Albright were blasting the secret knowledge to baby boomers everywhere.

es misunderstood by those who require a more streamlined approach to art and artmaking. Mail art is all-inclusive and therefore it can be voluminous. But those who stick around, while unable to be categorized, possess a similarity, a certain openness that makes mail art work--for themselves and for the ever-shifting whole. Into this den of iniquity I unknowingly walked in 1978 and there to greet me were the likes of Zack. I now have a box full of his rambling ten page letters that always go one better than each of my replies. They still fascinate the hell out of me because they document my becoming ensnared in the magical world that was the Network in the 1980s. Zack assigned me, like all of his correspondents, to one of his Correspondence Novels. I was part of CN8: Ezmeralda. I didn't know it at the time, but that text, whether conceptual or real, would tell, among a great many other tales, the story of my important journey of self-discovery through mail art, a way I unexpectedly and imperfectly found my voice. Though an audio cassette with a colorful cover that I made for a woman I met in Barcelona whose name happened to be Esmeralda was the only tangible link to the name of Correspondence Novel 8, somehow, somewhere, this field of ephemera that lived in David Zack's mind (and archive, if it still exists) contains the blueprint for an archetypal time of my life that could be read like a… novel.

es misunderstood by those who require a more streamlined approach to art and artmaking. Mail art is all-inclusive and therefore it can be voluminous. But those who stick around, while unable to be categorized, possess a similarity, a certain openness that makes mail art work--for themselves and for the ever-shifting whole. Into this den of iniquity I unknowingly walked in 1978 and there to greet me were the likes of Zack. I now have a box full of his rambling ten page letters that always go one better than each of my replies. They still fascinate the hell out of me because they document my becoming ensnared in the magical world that was the Network in the 1980s. Zack assigned me, like all of his correspondents, to one of his Correspondence Novels. I was part of CN8: Ezmeralda. I didn't know it at the time, but that text, whether conceptual or real, would tell, among a great many other tales, the story of my important journey of self-discovery through mail art, a way I unexpectedly and imperfectly found my voice. Though an audio cassette with a colorful cover that I made for a woman I met in Barcelona whose name happened to be Esmeralda was the only tangible link to the name of Correspondence Novel 8, somehow, somewhere, this field of ephemera that lived in David Zack's mind (and archive, if it still exists) contains the blueprint for an archetypal time of my life that could be read like a… novel. ipants of a show Eric Findlay put together in the UK) CN-4: 6 Finger Chicken Tales (a reference to the Neoist concept of a six-fingered hand) or finally, CN-9: The N-Tity (enough already said). The rest were named for one or more of the major loci of the Network: CN-3: Rod Summers RAF VEC (named for the Dutch sound artist) CN-5: Leavenworth Jackson: Illustrator (An attractive, female, SF-based rubberstamp maven among other things), CN-6: Bern Porter and other geniuses (Porter worked on the Manhattan Project, helped invent early TV and was the first American publisher of Henry Miller) and CN-7: The Bedside Ackerman (named for the previously-quoted creator of thousands of hilarious and neo-Noir texts and drawings guaranteed to drive even the most deranged mail artists slightly out of their mind.)

ipants of a show Eric Findlay put together in the UK) CN-4: 6 Finger Chicken Tales (a reference to the Neoist concept of a six-fingered hand) or finally, CN-9: The N-Tity (enough already said). The rest were named for one or more of the major loci of the Network: CN-3: Rod Summers RAF VEC (named for the Dutch sound artist) CN-5: Leavenworth Jackson: Illustrator (An attractive, female, SF-based rubberstamp maven among other things), CN-6: Bern Porter and other geniuses (Porter worked on the Manhattan Project, helped invent early TV and was the first American publisher of Henry Miller) and CN-7: The Bedside Ackerman (named for the previously-quoted creator of thousands of hilarious and neo-Noir texts and drawings guaranteed to drive even the most deranged mail artists slightly out of their mind.) There was no direct answer but there were many drawings--of heads inside of heads, heads smoking, heads talking and smiling, heads that decorated lettering and vice versa. I did learn that my CN was named for Ezmeralda Brez, a little-known South American artist. Zack would gladly tell me things about her from time to time and mention others who were in my CN, but in the end it was up to me to provide the meaning and shape of the CN by just being myself. In retrospect, this was an interesting and timely idea for chronicling what was happening in the network at the time, though it was a little baffling to be immersed in it, which we all were. Were they to be presented coherently, I suspect that we would see now that each Correspondence Novel did have its own particular vibe and told a particular story--as reflected through the list of seemingly randomly-generated participants, even if the storylines were as rambling and boundary-less as Zack's letters, writings, drawings, mind and ensuing reputation.

There was no direct answer but there were many drawings--of heads inside of heads, heads smoking, heads talking and smiling, heads that decorated lettering and vice versa. I did learn that my CN was named for Ezmeralda Brez, a little-known South American artist. Zack would gladly tell me things about her from time to time and mention others who were in my CN, but in the end it was up to me to provide the meaning and shape of the CN by just being myself. In retrospect, this was an interesting and timely idea for chronicling what was happening in the network at the time, though it was a little baffling to be immersed in it, which we all were. Were they to be presented coherently, I suspect that we would see now that each Correspondence Novel did have its own particular vibe and told a particular story--as reflected through the list of seemingly randomly-generated participants, even if the storylines were as rambling and boundary-less as Zack's letters, writings, drawings, mind and ensuing reputation.

m.”

m.”